A journey to Kubernetes with Consul and Kong at an Enterprise

Introduction

It has been quite a while since the last time I have written something this long, especially in English that is not my mother tongue, so I hope I can keep you interested long enough!

I basically wrote the whole thing but realised it might be good to put 2 things in context upfront:

Who am I? Professionally, I have been working as an IT Consultant, basically in 2 companies: Accenture for 10+ years in my home country, Brazil, followed by a smaller great company called Fastlane Solutions in Australia for 7 years and now working for one of Australia's "big 4" banks as we call. My official company title is Managing Consultant (Cloud / “DevOps”) but I call myself an Automation Engineer. I do not come from either Development nor Operations background and since my first job / project I have been automating things: from a PHP site to facilitate mobile testing 17 years ago in my internship, through test automation using QuickTest Professional with Basic coding, Mainframe automation with Rexx and then joining the area I have been at for the past 13 years called Development Control Services (from practices called Software Configuration Management, Configuration Management/Provisioning, Build/Deploy/Test automation, Release Management and Monitoring) which then became the DevSecOps/SRE/Platform Engineering.

Why am I writing this? I have participated in small but mostly medium and large sized projects and I often find that the journey and important things learned along the way are usually taken for granted, especially once you have to go to your next “gig” right after from a Consultant point of view or if you can’t share much from an Enterprise point of view. Personally, I think I have been allocated for most of my career except for a 2 month break when I moved to Australia and a few occasions where I was not billable but still doing planned work (I am not counting annual leaves, these are a must for me). For a very long time now I have a 1 week break where I don’t have anything planned, so I thought I would spend my time sharing part of the 2 years journey I was part of and hope to provide some useful information and insights to whomever is planning or going through a similar case. Yes, I know most people do that as part of their work and I hope both me and customers/companies I work for have the same mindset going forward, it is mostly about initiative, people are keen to share.

If you are still with me, this introduction is to understand some of the decisions made that might even steer you in different directions, so if you start from the other parts you might want to come back here if needed for clarifications. I can’t provide details about the company, but suffice to say it is a large organisation with as many regulatory requirements as you could wish for, which should give you some idea on what it encompasses and why it took longer than one would think to migrate.

Backgound and context

It all started around 7 years ago, I was not there, but the idea was to create a platform where developers could deploy APIs and Single Page Applications (SPAs) seamlessly without worrying much (or at all) about the underlying infrastructure, very similar to what people call Internal Developer Platform (IDP) these days. Architecturally, after proper design, security endorsements, planning and a lot of work was basically built with the following components on premises just looking at API hosting (that remain today):

GTM

F5 Load Balancer

Nginx: with a commercial WAF on top of it, coarse grain JWT validation, CORS and some other bits that are convenient to have in Nginx as opposed to anywhere else

Axway Gateway: the API gateway with proper swagger definitions, basic auth with applications that group consumers and some other specific policies for edge cases

Hashicorp Consul: used to map Nomad jobs (as they have unpredictable ports) and basic key/value store

Hashicorp Nomad: running the actual docker containers

Provisioning:

vRA with some automation on top

Ansible

“CICD”:

Atlassian Bitbucket

Atlassian Bamboo calling mostly Python code

jFrog Artifactory for artefact management and mirrors (with Xray for scanning)

Some security scanning tools

Some unit, contract and system testing tools

“Observability”:

AppDynamics for container metrics

Splunk for logging, monitoring and alerting

Catalog: a NodeJS portal backed by APIs in the same platform, this was very much ahead of its time in my opinion, you could compare it to backstage back in the day and now it is even more than that in some ways.

Developer tools: a Python CLI for developers to generate, build and deploy stuff from the comfort of their terminal.

As this platform evolved, some features were added that will help to explain some of the other decisions made:

Caching support with Redis Cluster for each API that needed one.

Simple eventing with Kafka.

Light datastores using Cassandra / MongoDB.

5 years ago that platform had already been migrated from an older generation of on premises Data Center to another one. Around 2 years ago, for many reasons that are not relevant for this article, it was decided that the existing (second) on premises hosting platform would be decommissioned and another one was being created (3rd iteration for our platform). The important point here is that given a migration would need to happen, the consideration of moving directly to Cloud came into picture given that it has already been discussed a few times.

The other point that has always been discussed, which seems kind of obvious, was the possibility of using Kubernetes instead of Nomad for container orchestration. The non-exhaustive list of the things that were considered is:

Did Hashicorp provide a turn-key PaaS option for Nomad? Back then the answer was no, so we would have to provision in Cloud VMs and that was probably not worth it unless we knew that we would overgrown our existing Data Center’s capacity somehow.

Nomad was working and scaling amazingly, why would we change the platform? This one is a bit trickier to answer, but a few things that have been considered:

Kubernetes does much more than what Nomad does: this can be considered good and bad, but mostly good in our analysis which turned out to be true specially when using redis-cluster using Helm as well as the other control-plane components.

All major cloud providers were offering Kubernetes and not Nomad as a service.

Also related to the points above, Kubernetes was evolving at a massive pace: again, good and bad, but mostly good.

Some “negative” points we have considered:

Steep learning curve for Kubernetes compared to Nomad.

Refactoring of our existing code (mostly new code in reality).

Risks associated with the change in the platform: can’t remember much here but an interesting one was a JDK in your base container that did not support cgroups2 which broke everything (in our environment) when we moved from Kubernetes 1.23 to 1.24.

After a lot of research, input and design we have decided that Kubernetes was the right thing to do, and the cloud provider was Azure (AKS). It is also important to notice that a separate team would be responsible for building the pattern for Azure and AKS and we would consume it (provisioned by Terraform - mostly - and some Azure DevOps).

By that time the platform had around 800 APIs (mostly Java and some in NodeJS) already in Production (now 1200), which meant:

We could not fundamentally change the way people develop and deploy - like mentioned above it is an IDP, so most things were transparent to developers (they did not know we were using Nomad and did not need to know we would be running Kubernetes).

We still needed support deployments to both platforms for a long time and still be able to add new features.

No one knew much about Kubernetes, but as Engineers do, we were excited to learn and tackle that “beast”. The team did some basic training research and we started outlining how the Nomad jobs / tasks would translate to Kubernetes objects and made some decision on other things we would use:

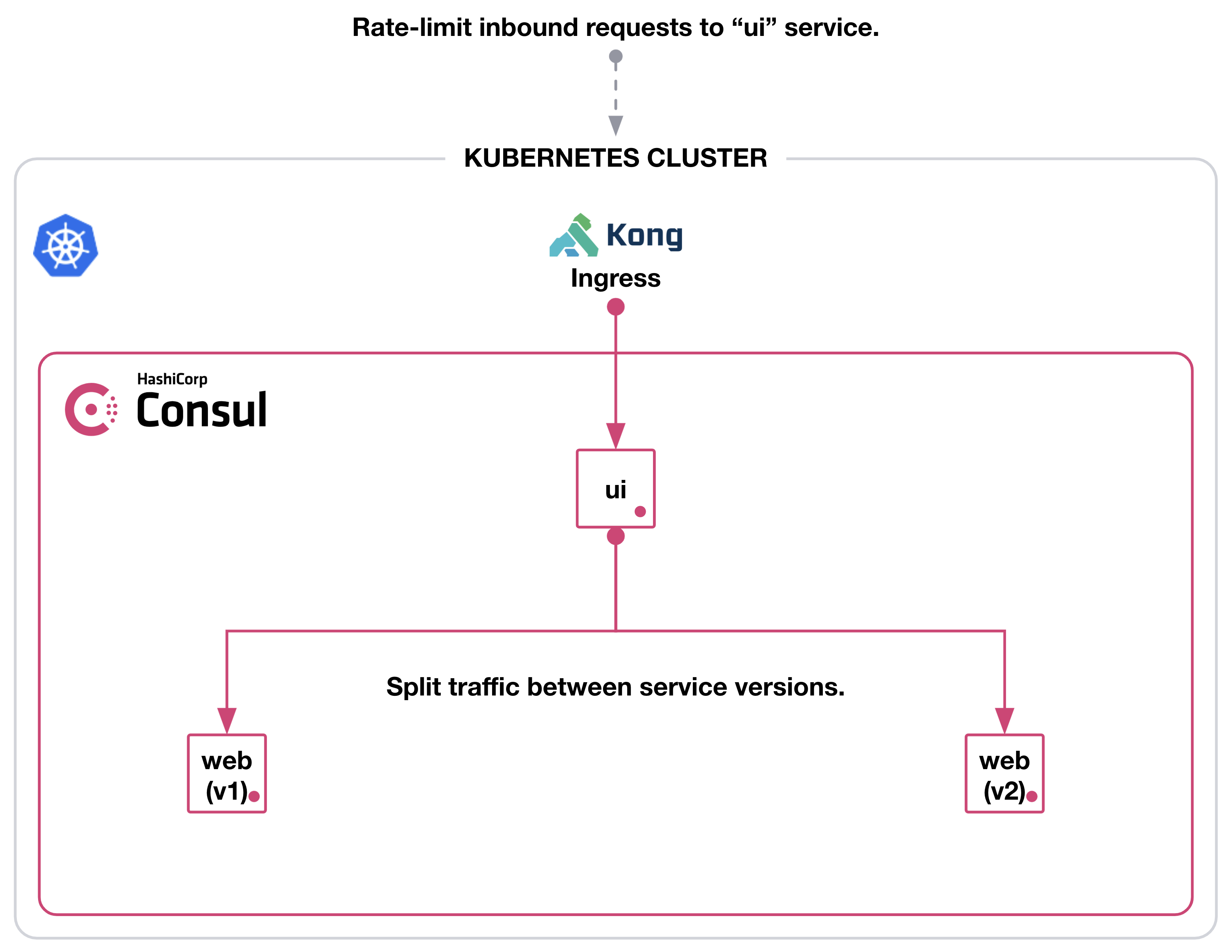

Kong Ingress Controller for Kubernetes: there were again many reasons for this decision, but the basic features we wanted from it were:

Fine grain JWT validation.

Basic Auth.

Rate limiting per consumer.

Kong Gateway / Kong Ingress Controller: the idea was for this to replace Axway API Gateway so this part would be the DBLess Kong installed on premises, and it would also route either to Kubernetes or to the legacy environment depending on where your API was.

Hashicorp Consul Connect (Service Mesh): we evaluated a few options back then, the most critical factors to that decision were:

Simplicity of setup: as compared to plain Istio / envoy.

Vendor support: as opposed to a third party (the fact that we were already Consul helped).

Works in Kubernetes but also on premises.

Has additional features: if we wanted to use them.

Splunk Connect for Kubernetes: for all logs that would go to standard output (including and mainly for the components above).

Fluent bit: for all our customer containers given we don't display to standard output but write to their own logs, so fluent-bit basically scrapes them via sidecar.

Each of these decisions were consolidated by technical “spikes” where we would test or at least confirm that the features we needed indeed worked for us. I will be adding specifics for each one on the individual series.

General automation approach

Aside the tools, I will try to clarity some other aspects on how we do things:

Provisioning: as mentioned before, there was another team managing the Enterprise Landing Zone to make sure there was a proper standard in terms of Subscriptions, Policies, RBAC, Firewalls, Subnets, etc. It was mostly done by Terraform which was also installing Helm charts, but we found that the latter caused some issues so we moved that to our internal bootstrapping process that would install base requirements plus our control plane components (below). That also gave us the chance of doing a partial “destroy” where we could uninstall everything without destroying the whole cluster which proved to be very useful while testing new components.

Bootstrapping: once we get a hardened AKS cluster with proper Policies, RBAC and SPN accounts set, we need to install everything that allows users to deploy to the platform, that consists of all the tools mentioned above, here we evaluated a couple of options:

GitOps (i.e., Flux and ArgoCD): because we promote releases one environment at a time, we wanted more control on when this was happening (see more on blue green), so we decided not to do it that way.

Kustomize: given all the products had helm charts it did not make sense for us to rewrite anything so working with standard Helm values was a better deal to track changes from upstreams.

Helm + “Kubernetes API”: this was our choice would give is all flexibility we needed and we did not need to add any new technology to the stack, however it has some downsides when compared to something like Argo / Flux, as an example, keep the platform updated but we still decided going this way and you will see more details on how below.

Platform provisioning automation: we already used Python for almost everything, so we decided to add the Helm values files as Jinja2 templates so we could customize things like replicas, resources/limits, hostnames and anything else by environment. This also proved to be handy for orchestration purposes as we did not want and could not have all of these coming up at once given their dependencies. Other orchestration concerns were related to Custom Resource Definitions (CRDs) and patches that needed to be applied after the chart was installed and sometimes even API calls (for Consul Terminating Gateway).

Application deployments: have also followed the same approach with Python making Kubernetes API calls to create the objects, the main reasons for that were:

Some things needed to be determined on the fly: i.e.: if one API grants consumption access to another API we need to check that before creating Consul ServiceIntentions and the same logic applies for access consumption groups in Kong.

We also needed to check for some other dependencies, as an example, if that API declared it needed Redis we would install its own Redis cluster with Helm during deployment time if it was not there.

Finally, we also need a predictable way to patch/upgrade and add new features, so we have decided to do blue / green for the cluster, the overall process was defined as:

Upgrade Kubernetes and all supporting features after a release has been cut: read “release cut” as the process of tagging/branching, publishing pip modules and making them available on the server that would bootstrap the new cluster.

Test that in an engineering environment (dog food).

Create a new release cut and do the blue / green process as below:

Create a new AKS cluster.

Bootstrap the cluster with all the tools.

Restore the latest backup from the active environment (we have backups every 12 hours for the applications namespace).

Run regression tests to confirm they are working the same way they are on the active cluster.

Flip the Azure API Gateway to the new environment.

Decommission the old environment after a couple of days if nothing bad happened, otherwise flip back.

If you got this far thanks for your time, I appreciate you might not have learned anything new at this point so please bear with me and proceed to the next topics which give a bit more details for each of the core components.

Implementation details by "tool"

Service Mesh with Consul Connect

The main objective was to control East-West traffic, initially by base path where API ‘foo” can call “bar” and later we also wanted to control traffic by operation and HTTP method. The other great advantage here is that the connection between all Pods goes via envoy using TLS so we do not need to worry about that.

Once more to avoid any overhead in terms of learning, implementation and complexity, we chose Consul Service Mesh as opposed to Istio, which from what we researched 2 years ago, was not as straightforward to configure. We have evaluated other options but given we needed vendor support, on premises support and the fact that we were already using Consul on premises it made the decision easier.

You are probably better off reading the Consul documentation which is pretty good, but I will give some overview about the Consul Custom Resource Definitions (CRDs) we have used:

Service Intentions: they basically allow you to specify which sources (plural) are allowed to a given destination and that specification uses Kubernetes service names. You can use something like pathPrefix (which is what we have used initially), or you can use pathRegex that can be specific to operations. For both, you can specify the method and get very granular level access control.

Service Resolver: does the matching of the service instances (service and service subset).

Service Router: layer 7 routing, defines the service subsets and the filters to select them.

Service Spitter: we did not use this one specifically, but you can use it to do canary testing as an example, say sending 20% traffic to the new version and the rest to the other one.

We have used Resolver and Router to create separate test instances of our services that would get traffic based on a http header to allow testing in the same environment without disrupting other consumers (we did something similar using Consul on prem and Nginx in the legacy platform).

We have made a few changes to the Helm values file at the beginning, the main ones highlighted at the basic installation and Security, such as:

gossipEncryption.autoGenerate: true

tls.enabled: true

tls.enableAutoEncrypt: true

acls.manageSystemACLs: true

consulNamespaces.consulDestinationNamespace

storageClass: whatever is SSD given that Consul Server is IO intensive in some situations

containerSecurityContext.*.privileged: false

containerSecurityContext.*.capabilities.drop: [‘NET_RAW’] (you can be more specific here)

You might also need some special annotations, as an example if you want to expose it as an internal LoadBalancer in AKS you need to use the “service.beta.kubernetes.io/azure-load-balancer-internal” annotation.

To make calls outside of the Service Mesh (North-South), we have started trying to use the Terminating Gateway, however back then (2 years ago roughly), special clients like JDBC that maybe would connect to some endpoint that would present some alternative cluster endpoints and that did not work as expected. Hashicorp provided great support in understanding the need and to get this in, unfortunately due to internal deadlines we have to proceed without this one, kudos for Hashicorp Team on all levels not only for that but also for general support.

For the reasons above, we have decided to go with the simple approach of using Exclude Outbound ports where we basically determine what our service needs to access and add the IPs to the exclusion.

Important note is that in order to enforce mesh destinations only you need this.

Ingress Controller with Kong for Kubernetes

As highlighted in the Introduction to these series, we were already using Axway Gateway and Nginx for most things. The same way we did for the Service Mesh, we wanted a Gateway that was modern with both Cloud and on-prem Support with the basic features that we needed:

Ingress controller

Basic Auth support by consumer

JWT Auth support (static and dynamic)

Rate limiting

We also considered the fact that Kong was DB-less and Kubernetes was a great thing, however there was an unforeseen issue with that and it will be explained later.

Also, I won’t be mentioning details about the on-prem DB-less installation as it is not very relevant to this article, but it served us well on understanding how Kong works given you have a single file with all the configurations (as opposed to CRDs in Kubernetes that are driven by fragmented objects of different types).

As an Ingress Controller, Kong works very similarly to Nginx or any other ingress where you provide an annotation at the Ingress/Service (i.e.: kubernetes.io/ingress.class: "kong"). Other than that, you specify common things like path and operations as well as more specific things related to CRDs.

For the Basic Auth part, you can use Kong Consumers and do this in many ways, but basically the way it works is:

Create the basic-auth KongPlugin (generic that sits in the same namespace as the service/ingress)

Create a pair of ACL and credential for a particular consumer (Kubernetes Secrets)

Create a KongConsumer that puts together the acl and the credential

Use the basic-auth and the KongConsumer in your ingress / service provided that they have the “kubernetes.io/ingress.class: kong”

You can optionally create consumers that combine multiple ACLs and credentials and use that on the Service/Ingress instead of a standalone Consumer

You can also refer to this Kong example but it is not using Consumers.

The JWT Auth configurations using the OpenID deserves it’s on article but the one thing I need to mention here is that if you are planning to use the jwt-signer please make sure that is really what you need because, as the name clearly says, it (re)signs the JWT and that might not be exactly what you want. In our case we only wanted it to be validated against specific ISSs using Dynamic endpoints and/or static JWT keysets.

The Rate Limiting Advanced can also be worked out in many ways and it is fairly “simple” to configure, however we had a big issue due to the way the CRDs work as per this invalid configuration. This “breaks” Kong and, prior to Kong Ingress Controller 2.10 and Kong EE 3.2.2.3, it did not tell you what was inconsistent and only showed a primary key error. This has just been recently improved in a way that now you get a Kubernetes Warning event showing what has been broken, but it still requires manual intervention to fix the environment and allow new deployments to resume properly. Also, because of the nature of the type of issue, it can’t be validated by the webhook, at least not at this point (we have a ticket open with Kong Enterprise support).

A few non-vanilla configurations we have done for Kong on the Helm chart are:

userDefinedVolumes: with internal ca certs

prefixDir.sizeLimit: when you scale (we have thousands of Kong objects) this dir get full, we have it set for 2Gi but if you see this error in Kong startup it might be time to change the default value (256Mi): “Warning Evicted kubelet Usage of EmptyDir volume "kong-kong-prefix-dir" exceeds the limit "256Mi".”

ingressController:

dump_config: true # Enable config dumps via web interface, we need that due to the issues mentioned above for investigation

feature_gates: CombinedRoutes=true # Enable feature gates to keep routes under service

proxy_timeout_seconds: "600" # Increase the timeout for controller config, we need that because we have thousands of objects and our restore was going over the default limit

proxy_sync_seconds: "10" # Increase the number of seconds between syncs, default is 5s

admissionWebhook: # we don’t apply the Kong config it is not valid

enabled: true

failurePolicy: Fail

Environment: # we have added many variables here but this is very specific to our use case, but I will just list them here

lmdb_map_size: "512m"

log_level: "info"

anonymous_reports: "off"

mem_cache_size: "512m"

ssl_cert: "/etc/ssl/private/lbcert"

ssl_cert_key: "/etc/ssl/private/lbcert"

nginx_main_worker_rlimit_nofile: "300000"

nginx_http_client_header_buffer_size: "32k"

nginx_http_large_client_header_buffers: "8 64k"

nginx_http_proxy_buffering: "off"

nginx_http_proxy_buffer_size: "32k"

nginx_http_proxy_busy_buffers_size: "64k"

nginx_http_proxy_buffers: "32 8k"

nginx_http_proxy_request_buffering: "off"

dns_valid_ttl: "180" # without this we were getting loads of DNS warnings

# admin configs, again mostly because of our large number of Kong objects

nginx_admin_client_max_body_size: "0"

nginx_admin_client_body_buffer_size: "30m"

We have also applied a few CRDs that were generic after the helm chart installation:

KongClusterPlugin:

acl-deny-all: acl as global with allow as ["x"] and hide_groups_header as true. This is important in the case you misconfigure anything so it blocks any requests without authentication

cors: marked as global to do some basic CORSs checks for all methods and preflight_continue as false

KongPlugin:

acl-allow-all-component: acl plugin with deny as ["x"] and hide_groups_header as true to allow calls without credentials for specific components. This is used for things where you don’t specifically want authentication (see below)

request-termination: we created a health check to ensure Kong was up with status_code 200 and message as “success” backed by an Ingress pointing to the “kong-proxy” service with the plugins basic-auth-anon-infra, healthcheck-request-termination, acl-allow-all-component

Apart from that we had to apply this path as per this document to keep compatibility between Kong 2.X and 3.X.

Consul and Kong implementation specifics

Configuring Kong to be part of the Service Mesh is not very hard and the Hashicorp blog post on this is very good, however it is important to highlight a few extra things, especially given it is a bit outdated.

The main changes on the Kong Helm chart are as follows:

podAnnotations:

consul.hashicorp.com/connect-inject: "true"

consul.hashicorp.com/transparent-proxy-exclude-inbound-ports: 8443,8080

consul.hashicorp.com/transparent-proxy-exclude-outbound-cidrs: <anything Kong needs to connect to directly that is not part of the Service Mesh>

consul.hashicorp.com/sidecar-proxy-memory-request: you need this as you scale and set this here as the envoy sidecars for your application pods don’t need much resources but this does

consul.hashicorp.com/sidecar-proxy-cpu-request: as above

consul.hashicorp.com/sidecar-proxy-memory-limit: as above

consul.hashicorp.com/sidecar-proxy-cpu-limit: as above

proxy.annotations:

service.beta.kubernetes.io/azure-load-balancer-internal: "true" # Same as mentioned for Consul

service.beta.kubernetes.io/azure-load-balancer-health-probe-request-path: /healthcheck # Also very Azure specific

labels:

enable-metrics: "true"

consul.hashicorp.com/service-ignore: "false" # you need this when you have services that don’t match the deployments

Given we have blocked all non-explicit connections in the Service Mesh, you need a Consul ServiceIntention that allows Kong to access any API in the service mesh, as it is the "front door" as per this example.

Logging

Given we were already heavily using Splunk for logging we have decided not to use Azure Insights, so we have approached logging in 2 ways:

Logs for the control plane (what we call infrastructure namespace) and had things like Consul and Kong are scrapped by Splunk Connect for Kubernetes

Given our container logs don’t get sent to standard output but log files inside the container, we decided to use fluent-bit.

As you have probably noticed Splunk Connect will reach End of Support on January 1, 2024, so I am not going into details about it, it is fairly simple to install and configure and I hope it’s successor also is.

For fluent-bit I would just like to do a couple of remarks:

Defaults work well for most things and on scale

We have separate config for each container type and decide which configuration to use on the fly (Java + Tomcat, SpringBoot, NodeJS, dotnet core)

INPUT

Skip_Long_Lines: we kept it On

Mem_Buf_Limit: we kept it as 50Mb

Refresh_Interval: we have set that to 5 (seconds) for logs that rotate by creating new files (i.e. dotnet core), for the logs that rotate on the same file it works fine with defaults

We have set requests/limits based on our container requests/limits:

Minimum:

Memory: 96Mi

CPU: 25m

Maximum:

Memory: 288Mi

CPU: 100m

The other thing we have decided to do is to use Prometheus and Grafana to gather proper metrics from the envoy sidecars that work pretty much out of the box once you enable it in Consul. The Dashboard setup is a bit cumbersome but if you know your way around these tools you should be able to do it in no time.

On that note, because we use Policies to secure Kubernetes and did not want to monitor system node pools, we had to add the following to our Prometheus node-exporter:

hostIPC: false

hostPID: false

affinity:

nodeAffinity:

requiredDuringSchedulingIgnoredDuringExecution:

nodeSelectorTerms:

- matchExpression:

- key: agentpool

operator: In

values:

- usernp1

Also make sure to enable the Push Gateway as this is the current standard on how Consul pushes these metrics to Prometheus.

The other annoying detail was importing existing dashboards from grafana.com, importing as is and setting/updating the datasource did not work, we had to manually replace any “datasource” entries with our datasource name, I guess there is a better way to do it but I could not spend too much time on this.

In the end of this exercise by the time we had our first real customer other than ourselves, this is how things looked like:

Versions:

Kubernetes 1.25.5 and 1.26.3 - platform release in progress so it will all be 1.26.x in a couple of weeks

Consul k8s helm 1.1.2 (Consul 1.15.3 and envoy 1.25.6)

Kong for Kubernetes helm 2.23.0 (KIC 2.10 and Kong Gateway 3.2.2.3)

Fluent-bit: 2.1.4

Splunk Connect for Kubernetes: 1.5.3 - we will be replacing this with Splunk OpenTelemetry Collector for Kubernetes

Scale:

For Production, we have a minimum scale of 3 for any Deployment (with TopologySpreadConstraints to spread across AZs). The containers for the deployments have:

The application

Nginx

fluent-bit sidecar

consul dataplane envoy

The expectation is that Production should have around 100 Standard_D16s_v3 nodes when the migration is done for 1200 APIs.

The tweaks done in terms of scaling other the ones mentioned above for Kong, Consul and fluent-bit were mostly around requests / limits and scale, some examples for Production:

Note that we have special settings for the Kong consul dataplane as that one works much harder than the API sidecars as it is the front door.

You can play with most things here yourself, I am providing some samples on this repository. They have most things mentioned here except from Splunk in 2 forms:

Local setup, where you can use MetalLB to get an internal “LoadBalancer” and Longhorn for Persistent Volumes (I am leveraging this awesome homelab repo on my home cluster with 5x Dell Optiplex 9020m).

Linode Kubernetes Engine (LKE) from Akamai Connected Cloud: one of the fastest, easiest and cheapest ways you can get a Kubernetes cluster to play around with, so I will provide some Terraform code but it is very straightforward via UI as well for this purpose.

Comments

Post a Comment